3. How can urban construction affect natural cycling of storm water? How to accomplish harmonious management between people and nature?

The type and speed of urban construction can have a huge effect on the natural cycling of storm water. In the People’s Republic of China (PRC), urban planning has frequently not included sufficient storm water provisions. Many cities have developed quickly, with a tendency to expand outward rather than by increasing density. City development increases impervious pavement and decreases storage areas, resulting in increased runoff in urban areas.

Drainage systems that were designed to meet the needs of the original service areas are unable to carry extra storm water runoff from newly paved areas in the catchment area. The increase of storm water from the newly developed areas in upstream areas overloads the existing pipelines downstream, leaving storm water with no place to go.

As cities expand outward, rivers that used to be in rural or peri-urban areas become urban rivers. With this, the water-carrying and storage capacity of these rivers decreases due to siltation and possibly garbage if the city has poor solid waste management, as well as the encroachment of development, namely buildings, highways, and bridges. High intensity land development changes the surrounding natural terrain and topography, and alters the natural flows of river systems, floodplains, and lakes.

This is one reason that the Sponge City concept that is being pursued in the PRC is so important. The Sponge City pilots will hopefully demonstrate that investment in ecologically-designed storm water management practices should be used in all Chinese cities. Known as “Green Infrastructure” or “Low Impact Development” (LID) in Western countries, the basic principle is to minimize the impacts on natural and ecological systems caused the development and construction of artificial systems, such as drainage channels and pumping stations. LID aims to simulate natural ecological conditions through the storage, infiltration, evaporation, retention, and reduction of surface runoff, thereby increasing groundwater replenishment. LID minimizes runoff and nonpoint source pollution (NPS) caused by rainstorms by using decentralized and small-scale source control mechanisms and appropriate technologies. The objective is to maintain, as much as possible, the pre-development conditions of the natural environment and hydrological cycle.

4. In the field of urban storm water management, are there any cities that have made great progress?Are there any useful experiences that we could learn from?

I recently returned from a trip to the Netherlands and I was very impressed by the Dutch experiences in water management. It is well known that the Netherlands has a long history in managing the relationship that their country has with the sea, reclaiming large areas of land through the use of dikes, levees, and the traditional Dutch windmills. What is less widely known is that the country is essentially a large delta for the rivers Meuse, Rhine, and Scheldt. Additionally, over 80% of the population is urban and the country has a high average yearly rainfall rate, making it very important for Dutch cities to manage storm water and river levels to prevent flooding.

Of the cities with the most aspirational approach to their storm water management is Rotterdam. Located in the delta of the Rhine and Meuse Rivers, Rotterdam has taken a very active and holistic approach to managing their vulnerabilities to not only flooding by also the potential climate change impacts. Under most models, climate change will affect not only the frequency, but also the intensity of rainfall events. The impacts of climate change on local weather patterns are already being felt, but few cities have had the political will and resources to plan for the potential impacts. Since 2013, Rotterdam has had its own climate adaptation strategy which required the identification of local vulnerabilities and created a framework for future resilience planning and investments.

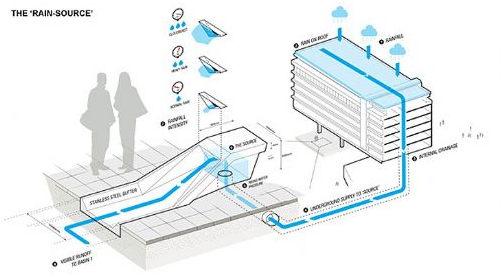

Recognizing that the city’s traditional flood defenses as being inadequate for future risks, the city began to access other ways to collect and channel storm water to prevent localized flooding. The interventions in Rotterdam range from small scale – such as supporting the development and planting of green roofs and rainwater harvesting– to large scale, such as the redesigning of their existing dikes to allow for multipurpose uses.

Innovative projects related to reducing flood risks in Rotterdam, such as the Benthemplein water plaza, have gained global recognition among urban planners. Integrating public recreational space, greenery, and water storage, Benthemplein water plaza was the world’s first large-scale water square. A multi-level space with different seating and activity areas, the plaza becomes a water reservoir during heavy rains. Wide gutters collect rain water and funnel it towards the deeper basins of the park for collection. The basins allow for the rainwater to be reabsorbed into the ground over a 24-hour period; in cases of extreme rain events, the water is drained to a nearby water way, thereby reducing the load on Rotterdam’s sewage system.The park with its substantial greenspaces and public spaces for sports and socializing has revitalized the area around it and become popular with local students and residents.

Overall, I think that Rotterdam serves at an excellent example of storm water management for cities in the PRC, not only for their holistic climate-aware approach to risk, but also for the integration of small scale efforts such as green roofs. Every drop of water that is reabsorbed in the city can have an impact on local and downstream flood prevention.

中国城镇供水排水协会(中国水协) 住房和城乡建设部城镇水务发展战略国际研讨会指定网站 国际水协会中国委员会工作网站

全国中长期科技发展十六项专项之一、中国十六大中长期重点专项 - 中国水体污染防治重大专项发布网站

技术支持:沃德高科(北京)科技有限公司 Copyright 2003-2011 版权所有 京ICP备12048982号-4

通信地址:北京市三里河路9号城科会办公楼201(100835) Email:water@chinacitywater.org Fax:010-88585380 Tel:010-88585381版权所有: 水世界-中国城镇水网